This is the text of a lecture I gave at Liverpool John Moores University on Match 11th:

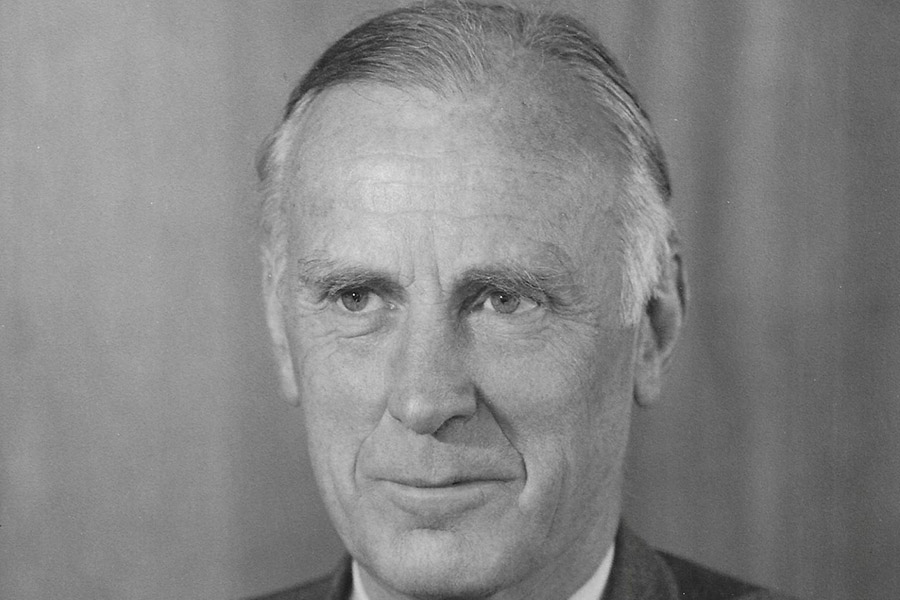

George Goyder – practical prophet and early champion of the responsible company

Introduction

Good morning. Great to be in Liverpool this morning to share with you the ideas and achievements of my father – a remarkable man. A man who has also had a huge influence on my own life and work. You could say that I have ended up carrying on the family business – a business whose subject matter is responsible business and sustainable wealth creation. At various points in this lecture you will be able to trace this influence, and I will refer in particular to Entrusted – the book I wrote recently with my colleague Ong Boon Hwee. i

I am very proud to be the son of George Goyder. He was way ahead of his time. He was a practical prophet. He called out the failings of capitalism 70 years ago.

Capitalism had always had its critics. George Goyder was different. He worked inside the system and had constructive ideas about how to change capitalism for the better. He could see the global financial crisis coming. He could see that the solutions being offered by governments in the decades after the war were not going to work. He was not just a thinker. He was also a doer. He worked with others to suggest different and better solutions. He got his ideas out there. Today I have been asked to talk about his life, his ideas, how they fit in with today’s ideas about corporate responsibility, and finally how they relate to the work I have done and to other peoples thinking about the future.

Part One – George Goyder’s Life

George Goyder was born in 1908. For those of you from round here who follow Liverpool Football Club that pins his date of birth just five years after Bill Shankly’s and if you follow Everton you will know that he was born just two years after Everton first won the FA Cup!). As it happens his sporting interests were athletics and rugby and tennis, although I do have happy memories watching the 1970 World Cup with him on TV.

His father William was a footloose entrepreneur. He had started, grown and on some occasions lost businesses in textiles and retail. He married a well-educated Swiss woman, Lili Kellersberger. She was also long-suffering. She endured moving 20 times, including across the Atlantic and back, in the first 21 years of their marriage! When Gordon Selfridge, the founder of Selfridges, came to London to start a store here, he was looking to hire a dynamic general manager and the man he hired was William Goyder.

His father was impatient of higher education. He was happy to see George study at the LSE but didn’t see why he should waste his time getting an actual degree!

George crammed three years of study into two at the London School of Economics. Leaving without a degree left him with some regrets, but also a lifelong determination to go on educating himself. After leaving LSE he worked, unhappily, in a paper mill in France. This was a terrible employer. As he tells us in his autobiography.

‘We worked round the clock in twelve-hour shifts, although this was illegal. When the gendarmerie periodically surrounded the factory on horseback, all work instantly reverted to the statutory eight hours. Anyone telling the truth would have been sacked next day. One Friday – pay – day I sat at my desk with the manager opposite. In walked a bulky French worker and demanded to see the patron about his pay. The manager signalled to me to keep my head down. Neither of us moved. The worker produced a rifle and pointed it at my head from about six feet. After some angry mutterings the worker left the office and fired off his gun outside’ ii

He then decided to seek his fortune in the USA in the immediate aftermath of the great crash of 1928. He ended up working as an office boy for the export manager of International Paper, one of North America’s largest companies which sold a quarter of all the newsprint produced in the USA.

Soon he was promoted into role of ‘executive apprentice’ and not long after he was, he was being sent around the world to meet and earn the trust of newspaper proprietors with whom he was negotiating contracts for the sale of newsprint. Remember this was an age before even television, where newspapers were THE means of communication.

Before he was 30, he was back in the UK, establishing British International Paper (BIP). He became Managing Director. At the start of the second world war, with the advent of the Coalition Government, Lord Beaverbrook, the owner of the Daily and Sunday Express newspaper, became Minister of Supply.

He recognised the importance of keeping the supply of newsprint and therefore of newspapers. He consulted the newspaper owners and they told him that the man they would trust to do this was George Goyder. So, he moved from his private sector job to become CEO of a hybrid organisation – the Newsprint Supply Company (NSC). NSC’s purpose was not to make a profit. It was entrusted with the responsibility of serving the whole newspaper and communications industry by organising the convoys that of newsprint ships that would cross the Atlantic under attack from German submarines, and then storing, rationing, and fairly supplying the British press with paper. I remember him telling me how he arranged to spread the risk of bombing by having small quantities of newsprint stored under tarpaulin on farms up and down the country, rather than concentrated in warehouses near the docks.

After the war George Goyder was offered other jobs, including manager of The Times, the country’s most prestigious newspaper, but he declined the offers. Instead, shrewdly, he negotiated a flexible contract with International Paper which allowed him freedom to do many things apart from his day job. He was active in the Church of England – he successfully championed the reform of its governance achieving a shift of power away from the Bishops to the lay members of the church, but that’s a whole other story! He also loved the art and poetry of a little-recognised man called William Blake, and founded the William Blake Trust which brought Blake’s work to the forefront.

And he and Rosemary had eight – yes eight! – children of whom I am the youngest. Five boys and three girls. You could get quite a good family game of cricket on the beach when we had family holidays in Donegal or Northumberland.

George Goyder wrote six books. He campaigned for the reform of company law, and many other causes. He retired from his full-time role at British International Paper in his sixties and died aged 88 in 1996. Let’s have a look at now at what he said in those books.

Part Two – George Goyder’s Writing and Thinking

As you know the Second World War was a time of great insecurity. At the start of the war there was a real fear of a Nazi invasion; that Jews would be rounded up and sent to concentration camps; that democracy would die and British people would come under the heel of Hitler.

Yet, as the war unfolded, this fear and anxiety was accompanied by a different mood. Not only a determination to work together to defeat Hitler, but also the suspension of party politics and short-term bickering, and the shared desire across many walks of life to ensure that Britain didn’t go back to the bad old days of the thirties, where there was extreme poverty, record unemployment, and poor education and housing.

There was no General Election between 1937 and 1945 and, as a result, there was actually a political breathing space in which people could think about a better future. My father was one of those involved in study groups at places like Oxford which were thinking about better social security, better housing, better town and country planning, better education and better business.

So, when you read about the 1944 Education Act, or the start of Town and Country Planning, or the Beveridge Report on social security, and all the great reforming achievements of the post-war Labour government under Prime

Minster Clement Attlee, or the formation of the NHS, it was in the wartime era that the foundations of thinking and policy and planning were laid.

My father was active in this; he was never primarily a party-political person, but he published a Fabian Society pamphlet in 1947 outlining some of his ideas for the reform of business. The Deputy Prime Minister under Clement Attlee was Herbert Morrison. My father remembered having lunch with Morrison and trying to persuade him that nationalisation of industry was not the answer. Changing the ownership did little by itself to improve the quality or effectiveness of the companies in question.

Then came the Cold War. During WW2 the alliance between the western allies and Stalin’s USSR was crucial in winning the war. Yet afterwards, as Churchill warned, an Iron Curtain descended. The countries of Eastern Europe – Czechoslovakia, Hungary Poland and so on – might have been freed from Hitler but they were now under the dictatorial heel of Stalin’s Communist party. From Churchill downwards, politicians made speeches about the evils of communism and the moral superiority of the West.

My father challenged this talk. He was no defender of the USSR or state communism, but he questioned the moral legitimacy of the capitalist system. He saw big companies were run for the financial benefit of absentee shareholders, rather than for some wider purpose. He believed that work was central to the dignity and well-being of human beings, and he saw too few companies which respected the contribution of employees. He disliked the insecurity of work; the way employers could hire and fire labour, seeing workers as means not ends. He was sympathetic to the role of trade unions in fighting for better conditions, better training and more security. The exploitative practices of employers had, inevitably given rise to a more militant trade unionism.

George Goyder deplored the waste that was caused by strikes and restrictive practices. There had to be a better way – a shared purpose to which employees, managers, owners and others could all commit.

Political parties were divided on ‘us and them’ lines. The Labour Party was the party of the working man and the unions. It talked about capturing ‘the commanding heights of British industry’ by taking them into public ownership. Steel, ship building, the docks, railways (does any of this sound familiar?) The Conservative Party was the bosses’ party, defending free enterprise, resisting nationalisation, keen to curb the rights of militant trade unionism and stop strikes and restrictive practices.

My father saw this as a wasteful and pointless conflict. Business, he argued, needed to find a basis on which all involved could work together to create wealth. And he described these ideas in that first book – the Future of Private Enterprise. Here is how it starts

‘Industry in the twentieth century can no longer be regarded as a private arrangement for enriching shareholders. It has become a joint enterprise in wh ich workers, management, consumers, the locality, government and trade union officials all play a part. If the system which we know by the name of private enterprise is to continue, some way must be found to embrace the many interests which go to make up industry in a common purpose. Since it is the legal structure of the company which determines its formal responsibilities to the parties to industry, we must examine the legal structure of the limited liability company and see to what extent it is capable of adaptation to make possible full co-operation between the parties to industry .on a basis of justice.’ iii

The Responsible Company 1961

He developed these ideas in The Responsible Company.

By 1961 the stakeholder debate was underway. It was not until 1970 that Friedman made his famous pronouncement that the only social responsibility of business was to make a profit, but the arguments were developing. My father sensed around him an increasing desire to justify massive rewards for the managers of businesses, and, in response, the growing strength of organised trade unions fighting for a fairer share of the rewards.

Because I spent my early adulthood listening to my father’s thoughts it always amazed me that so many people were taken in by Milton Friedman for so long. Friedman lived in an economist’s laboratory. I have no doubt he made an important contribution to economic theory but his pronouncements on the purpose of business betrayed an ill-informed and superficial view of business life. I doubt he drank many cups of tea in any works canteen. He never really stepped outside the theoretical confines of his profession, even to listen to his fellow academics from other disciplines. He traded punches with his theories about the purpose of business without any interest in the economic value or any understanding of the psychology of human motivation. He seems to have been a stranger to systems theory, an understanding of which would have taught him about the way business interacted with society. Nor did he seem to think rigorously about the pivotal role of law in regulating or steering human behaviour. In his world there were two compartments. One was occupied by commercial business and free markets and driven exclusively by the pursuit of profit. The other was the world of human welfare which was solely the responsibility of governments.iv

George Goyder might not have had a proper degree, let alone a doctorate but – unlike Friedman – he read widely and thought systemically. He took his philosophy of business not only from his own experience but from, among other sources, the interlocking worlds of philosophy, religion and jurisprudence.

From philosophy he took the idea of natural law and also of holism or systemic thinking.

Natural Law is the philosophy that certain rights, moral values, and responsibilities are inherent in human nature, and that those rights can be understood through simple reasoning. In other words, they just make sense when you consider the nature of humanity. One of the concepts that flowed from Natural Law was that if you owned property, you had responsibilities that went with the rights of the property owner. That was something else that never occurred to Milton Friedman when he talked about the supreme authority of shareholders. George Goyder often said that that ‘we should be talking less about ownership and more about ownership’

Holism is the theory that parts of a whole are in intimate interconnection, such that they cannot exist independently of the whole, or cannot be understood without reference to the whole, which is thus regarded as greater than the sum of its parts. Holism is often applied to mental states, language, and ecology. It is at its most obvious in medicine. Holistic medicine seeks to treat the whole person, taking into account mental and social factors, rather than just the symptoms of a disease. There is a perfect description of holism on a mural that I passed on my way to this lecture theatre. The inscription reads:

‘The eye cannot say to the hand: I have no need of you. Nor again, the head to the feet. I have no need of you.’

It is impossible to think of business in isolation from society. Society provides the soil within which business can flourish. Without education, literacy, the rule of law to enforce contracts and punish fraud, business could not prosper.

Systems theory has much in common with holistic thinking. It is an interdisciplinary theory about the nature of complex systems in nature, society, and science, and is a framework by which one can investigate and/or describe any group of objects that work together to produce some result.

From religion George Goyder he took many inspirations. He was a devout Christian. In the Old Testament he read about the Jewish tradition of Jubilee Release. This is the idea that, every 50 years, people should be freed from debt.

Here is how it is stated in the book of Leviticus.

‘You shall make the fiftieth year holy, and proclaim liberty throughout the land to all its inhabitants. It shall be a jubilee to you; and each of you shall return to his own property, and each of you shall return to his family. That fiftieth year shall be a jubilee to you. In it you shall not sow, neither reap that which grows of itself, nor gather from the undressed vines. For it is a jubilee; it shall be holy to you. You shall eat of its increase out of the field. In this Year of Jubilee each of you shall return to his property.v

This is a radical way of counteracting the tendency of an economy to become progressively more unequal. George Goyder applied this idea to equity capital. If I buy shares in the company, I gain an unending claim over the resources, wealth and direction of that company. To George Goyder this was wrong. The company should be able to earn its freedom from debt and the obligations that go with it. He saw shareholders as providers of capital not as legitimate permanent owners. He saw the perpetuity of the equity or common share as the fatal flaw in capitalism.

He helped to develop the constitution of the John Lewis Partnership. He helped another entrepreneur, a Swiss called Ernest Bader, who created a unique model of business in the Scott Bader Commonwealth.

Jurisprudence explores the logic and the philosophy that underlies law and legal systems. From his reading and experience Goyder concluded:

‘The law is regulative and its influence is positive. In the words of John Locke (Treatise on Human Liberty 1690 Bk 2 ch,–57) :- “Law in its true notion is not so much the limitation as the direction of a free and intelligent agent to his proper interest so that, however it may be mistaken the’ end of the Law is not to abolish or restrain but to preserve and enlarge freedom.’ vi

This approach informed his understanding of company law, something which many at the time – and still now – failed and fail to understand. Directors of companies may be elected – and removed – by shareholders, but their duty is owed to the company. Shareholders get their return if the directors successfully promote the success of the company.

Shareholders are referred to in company law as members of the company.

George Goyder believed that those who had worked in the company for a period of time had the right to be treated as members.

In the opening chapter of ‘The Responsible Company’ he wrote

‘The theme of this book is that the present system of law governing big business in the USA and Britain is out of date and must be altered. Company law must make provision for the representation of the worker. At present his not regarded as having any rights in, or duties to, the company…. One cannot complain if the worker’s attitude is irresponsible so long as he is legally excluded in his capacity as a worker from membership of the company No-one in the company other than the shareholders or the directors has any rights or duties under company law, and no-one but a shareholder is considered by law a member of the company. Company law does not recognise the worker.’ vii

To him the solution was obvious. Change the law so that employees became members, with a right to vote at the AGM.

Later in Chapter 8, he said

The primary task of the state in relation to industry is to set up the company on a basis of justice. And this means establishing a relationship of balance between the parties and then leaving industry to run itself so long as that balance remains reasonably effective.

My father was particularly concerned with the trend towards large scale operations, and industrial monsters big enough to undermine true competition. Supermarkets are a good example. Last week I was talking to a friend who used to supply strawberries to one of our largest supermarket groups. Late payment was a perpetual headache. Then if the supermarket decided it didn’t want a delivery, it could use one punnet of strawberries as an excuse. It would be these kinds of companies – he called them ‘Qualifying Companies’ that would be the particular object of George Goyder’s proposal for state action. At the same time,he expected to see companies in more competitive spheres naturally undertaking the steps he outlined in their own long-term self interest.

To turn these ideas in to practice he proposed that:

– every company must be required to have a General Purposes Clause and this must cover profitability, investment, the interests of customers, employees and the citizenship community – after a qualifying period of, say 3-5 years, employees be made members of the company with the right to vote at the Annual General Meeting and elect their representatives to onto the board – the board nominate one of their number to represent the interests of the consumer, and this obligation should be particularly strictly enforced in the case of monopolies like the railways or oligopolies like the energy companies.

The state should move to limit the size of dividends or pay-outs to shareholders, while encouraging the sharing of these with employees – The establishment of a ‘social audit’ so that a large company could ‘assure the Government and itself that it was discharging its social responsibilities in a proper way’. (Goyder says that the idea first came to him when talking to the Chairman of ICI in 1953).

His thinking about the responsible company was also shaped by his own experience in the Newsprint Supply Company. His wartime experience taught him a lot. He was working under a relationship of trust with the newspaper proprietors. He felt he was a trustee. He was entrusted by those people, to supply the raw material that keep the nation’s information and communication flowing. He wasn’t there to make an opportunistic profit for a short-term group of shareholders. He was there to create a form of long-term value from which his customers, and their customers, and citizens, and their government and the employees of the newspapers would all benefit. So, the concept of trusteeship was crucial to his view of the role of the board of a business. You will see that this is a concept which has lived and had great influence on me and on the work of Tomorrow’s Company, which I founded, and in turn on the way the responsibilities of both boards and shareholders are perceived. Here is George Goyder talking about the responsibilities of a trustee.

‘It does not matter that the beneficiaries may be future persons, presently unknown, or that differing rights may adhere to differing classes of persons, provided the object of the trust is clear. There may even be potential conflict between the rights of different beneficiaries. When a conflict arises, it has to be reconciled in as fair a manner as possible by the trustee. What is expected of the trustee is that he is conscientious. The word ‘conscience’ goes to the root of the legal principle of equity.’ viii

Goyder argued that directors of a company were trustees. They should be required in law to set out the purpose of the company in a general purpose’s clause. To hold directors accountable for fulfilling the purpose of the company, he envisaged the introduction of a social audit.

The Responsible Company is the first book in the English language to contain the proposal that companies should be subjected to what George Goyder called a Social Audit to go alongside the usual financial audit. As Goyder later described this proposal:

‘When we say that a business leader ought to act as a trustee, we are saying that he ought to be prepared to give an account of his stewardship, and this means a willingness to submit to outside appraisal. Just as today, the accountant examines the company’s books as auditor and makes his report upon the examination, so in the responsible company there will be social auditors to appraise the company’s social performance and to report upon it. Good management will welcome the opportunity at the Annual General Meeting to_ give an account of its stewardship or trusteeship; bad management will resist. The social audit should enable the public to distinguish between the two kinds of management, and set in train a process of free discussion about the company as a social organism and not only as a money-making machine.’ix

The Responsible Worker

George Goyder believed that human beings had dignity as individuals. He rejected the impersonality of large companies with absentee owners who treated workers merely as a factor of production. He saw that it was this treatment that had quite naturally led to the rise of trade unions. A worker needed to be able to fell fulfilled and emotionally secure. He developed his thinking about this in an award-winning book called The Responsible Worker which was published in 1975. By this time, I had left university and started work. As my father was finishing this book, it happened that I was getting first-hand experience of the issues that he was writing about. I got a short-term job working for the research department of a trade union – the AUEW (Engineering Section). At the next desk to me was a rather grumpy man called Jeremy Corbyn. While I was there, there was a strike, not of the research staff, but the clerical staff. I got myself into terrible trouble for speaking out against the ‘Victorian employment practises’ of the union at a meeting called by Hugh Scanlon, its General Secretary. At the end of the strike I was called in to see the Office Manager to be told that my short-term job was to be summarily terminated. I am pleased to say that Jeremy Corbyn came to my defence!

The Just Enterprise

All of these ideas came together in Goyder’s last book – The Just Enterprise:

‘The plea made in this book is for a new corporate philosophy. We need to see the company as an agent for social improvement, as well as a money-making machine.’ x

He then asked why the many successful examples of such an approach in practice – from Scott Bader to John Lewis Partnership to Karl Zeiss in Germany -had not been more widely followed. His answer is plain but not reassuring.

‘The usurious outlook, which treats a company as a shareholders’ property instead of as a living organism, simply cannot see the daylight. The ‘City’ view, with its preoccupation with short-term gains, is alien to the whole concept of industrial and commercial partnership over a longtime span.’

By the time this was published, in 1987, his youngest son – me! – was working as a manager in manufacturing. As it happened the manufacturing involved was newsprint. Perhaps it is not a coincidence that the name Goyder comes from the Welsh for forester! I will come back at the end to the language of forestry to describe the Goyder family thinking on trusteeship and stewardship.

Part Three – The evolution of the agenda

It will be clear from what I’ve said so far that terms like sustainability and Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) are not new. We are now bombarded by labels and slogans – a form of buzzword bingo that can deflect attention from the things that matter most.

Often the agenda is described in bits. Rarely do people bring together all the pieces in the jigsaw. Not enough holism, George Goyder would say.

The term CSR itself is a good example. It has attracted a lot of cynicism. That is hardly surprising when you google the term and come up with items like this.

Corporate social responsibility isn’t just about building reputations; it’s about building businesses that matter. How can CSR help you? And why are so many companies integrating it?

Whether you’re looking to add CSR to your business or want to increase your existing activities, download this white paper to learn more about how corporate responsibility can:

• Create Consumer Trust & Increase Sales

• Strengthen Brand Image & Loyalty

• Create Employee Morale & Attract Employees

CSR is so often seen as a tactic, a tool, a device for furthering a marketing or a business objective. That is not where the term started. Terms such as ‘social responsibility’ were being applied to the role of the manager as far back as the 1930s. Some of the people using the term were thinking systemically. Many saw businesses as part of a wider ecosystem.

The battle between those who see business as a servant of society, and those who see it as a free agent, goes back at least as far as the large-scale industrialisation of Britain in the early nineteenth century. You will have heard of the principled business owners like Robert Owen, who built companies that were designed to respect the needs of human beings, and to create community’s worth living in. Other examples include Joseph Salt in Bradford and Saltaire and, nearer Liverpool, Port Sunlight, created by Lever Brothers, and indeed the philanthropic and ethical approach of the Moores family whose contribution is recognised by the name of this university.

With each recent decade, the systemic thinking about the role of business in society has evolved, and with it have come new labels.

What hasn’t changed is the underlying belief that businesses cannot be judged on their commercial success alone. Business is there to serve human beings, in their many different and overlapping capacities – as customers, employees, suppliers, communities and shareholders, now and in the future. It is not there to exploit them. Nor is business about extracting short term financial gain regardless of longer-term consequences.

This underlying belief has, at different times manifested itself in different issues which are sometimes described by the label CSR. These have included arguments, battles and eventual breakthroughs over:

- slavery

- the treatment payment and safety of employees

- human rights

- the role of trade unions

- the rights of women, battles against discrimination

- the rights and wellbeing of consumers

the health effects of different products – for example the battle against lead in petrol or the fight to expose the true health impacts of tobacco. - conservation and industrial pollution and waste – Brent Spar.

- the impact of extractive industry upon indigenous populations

Sustainable development

In 1987 the UN published ‘Our Common Future’ a report by the World Commission on Environment and Development, a Commission headed by Gro Harlem Brundtland. This introduced and popularised the term ‘sustainable development’ that is “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs”

This emphasis on the needs of future generations has steadily deepened since. Emerging evidence of global warming, and equally disturbing descriptions of the loss of bio-diversity that deepened and widened the CSR agenda still further. Even some of the battles that may be thought to have been won in more developed economies continue in others, whether developed or less developed. Think about deforestation, palm oil, the threat to indigenous people in the Amazon. Other slogans have emerged. Some people have identified with ‘stakeholder capitalism’; others have used the language of the so-called ‘Triple Bottom Line’. Did they just react, issue by issue? How did they move beyond the reactive to the proactive?

This is where George Goyder’s ideas of corporate personality come in. Companies are like people. You don’t trust the person who waits to hear what everyone else is saying before they commit themselves, and then parrots the same words in order to win popularity. You don’t trust the leader who, like one we are told about in the French Revolution who looked out at the crowds and declared ‘Those are my people. I am their leader. I must go and follow them.’

You win trust by knowing who you are, where you stand and which relationships are most important to you.

Companies are like people. The companies which are best placed for competitive success in the longer term are the companies which know why they exist, what they stand for, and which are the relationships which are most crucial to their success. Every business has 5 key relationships – with customers, employees, suppliers, shareholders, and community. Every business stands or falls by the way its leaders handle those relationships .

That was the insight at the heart of the original Tomorrow’s Company report.

Once you see business through these eyes, the meaning of CSR becomes very clear. It is, simply, the way a company lives and practises its values consistently in all its relationships. And, surprise surprise, there is a growing body of evidence, which is covered in Entrusted and other Tomorrow’s Company publications, which demonstrates that this focus on purpose, values and relationships is central to success.

Part Four – The Responsible Company Tomorrow

What would George Goyder have made of all this? And what do I take from George Goyder’s work and beliefs in a search for a better capitalism?

A Better Capitalism

First, that we cannot escape the quest for a better moral basis for capitalism. It isn’t good enough to rant about what’s wrong with the current system. We need to go beyond criticism to creativity. George Goyder used the language of trusteeship. More recently Tomorrow’s Company and others have come to build on the same idea and have evolved a whole body of thinking around stewardship – something which Ong Boon Hwee and I have described in Entrusted.

Stewardship is a very old word, but in a world dominated by concerns about bio-diversity, climate change and sustainability, it has a fresh urgency. In simple terms stewardship means that we accept an obligation to pass things on to our successors in better condition. Or, to quote a native American saying, we do not inherit the world from our ancestors. We borrow it from our children. It is a value that you can find in the best run family businesses. Like the Japanese Hoshi Ryokan Hotel which has flourished for 46 generations or 1300 years. xi

Second, that you don’t find a better basis by trying to redistribute power within a system that is ridden with conflict. You have to go to the source of the conflict and redesign the company and the investment system and the law around a purpose that is worthy of wholehearted co-operation and commitment. George Goyder would say you have to find a more just or fair system in which human beings can feel motivated, even inspired to co-operate. They need to feel emotionally secure. That of course is far harder to achieve in a fast-moving global economy than in the world of the 1940s and 50s. Yet in an age of dangerous viruses, and terrorist threats maybe the pendulum is starting to swing back towards more regional and local forms of sourcing in which the benefits of human scale are better appreciated.

You also have to make the leaders and directors of a business truly accountable in all their key relationships. Formal accountability is to shareholders. Full accountability is something else: it is a matter of behaviour, not just governance good practice.

The language of class warfare may win some votes – attacking the rich, threatening to ‘take on’ the big global companies, ‘a shift in power from the few to the many’ but the test is whether such words or policies change anything about the purpose and values of the system or its underlying character. What mattered to George Goyder and what matters to me is the impact on the lives and experiences of ordinary people.

The same is true of ownership. After the war Labour tried to achieve a better character of wealth creation by changing the ownership. Yet the miners who went down in the pits to dig coal did not report feeling any better about the way they were treated by their management. Later we saw the other side of the same coin. Politicians of the Right tried to privatise the industries that Labour had nationalised. Mrs Thatcher and her free-market ideologues insisted that services like the railways would be more efficient when privatised. In reality this constant shifting of ownership has created a dog’s breakfast. The real losers from all this ideological musical chairs are the railway users and the taxpayer. I should know! I was interested to read in the Financial Times 10 days ago about the ‘re-nationalisation’ of Northern Rail, and the difficulties faced by other rail franchises. Guess what, rail experts are saying that the biggest improvement will come from freeing the management team from strictures of financial commitments from a franchise agreement. Roger Ford, industry editor of Modern Railways commented that “state control” can actually bring about flexibility and innovation. “You are freed from the need to tick off all the box ticking of what you’ve done. Staff can get on with innovation. You are run as a business instead of running it as a money-making machine,” he added. xii Exactly the language George Goyder used: it isn’t about being a moneymaking machine.

That is precisely the point. There are two kinds of state ownership, just as there are two kinds of private ownership. One treats companies as ‘moneymaking machines’ the other treats them as organisations with a useful purpose. The task is not to mess around with the ownership. It is to get the purpose right.

Authors like Colin Meyer have followed George Goyder’s example and argued for the encouragement of more trust-based companies like Indian based Tata and German based. Bosch.xiii A growing number of family business owners have started to create trust structures through which they hand over their business, John Lewis style, to an employee ownership trust rather than simply pass them on to their own children. A listed bank, Handelsbanken, has for many years been handing over a proportion of its profits into a trust held on behalf of its employees so that this trust is now its largest shareholder.

Thirdly we need to remember the importance of the commercial drive and the entrepreneurs who start businesses. We need to get away from the confusing language of ‘stakeholders.

In ‘Entrusted’ my co-author and I say why we don’t find terms like ‘stakeholder capitalism’ particularly helpful. The term stakeholder is so vague. It covers everyone from an employee deeply dependent on the decisions of the company to a resident of a district which is occasionally inconvenienced by delivery lorries. If you look in Wikipedia, you will even find some stakeholder enthusiast define the company as ‘a vehicle for co-ordinating stakeholder interests.

This makes no sense. No mention of entrepreneurs staying up half the night to bring a new product to market. No mention of invention, innovation, outstanding customer service making a business profitable. Just ‘a vehicle for co-ordinating stakeholder interests’ as if the company were some kind of local government subcommittee!

In a business the focus needs to be about contribution. What are we contributing to make this joint enterprise successful? The trouble about the emphasis on stakeholder capitalism, just like the exclusive focus on shareholder value is that both perspectives deal mainly with what these groups can take out of the company: not on what they contribute to its future success.

Ideas for a better capitalism have to go with the grain of the entrepreneurial process; terms like ownership and accountability have to be translated into legal arrangements, leadership practices, and ownership behaviours that truly put people first while still achieving economic efficiency and financial returns. As a company gets bigger, too often the ideals of the founders get sacrificed to the short term demands of the people finding the finance. The trick is to find corporate forms which underpin and reinforce the company’s purpose and values and character.

It therefore makes more sense to stick to the George Goyder idea that the company is a person, which thrives because it builds lasting relationships. It cannot thrive if it has conflict built into that personality. Purpose, values, relationships. These are the key building blocks of better companies, and better companies are building blocks of a better capitalism.

This leads on to a fourth insight we can gain from George Goyder’s work. Systemic thinking is vital. The world of business is not some kind of island banana republic, free to ignore its impacts on its own people or its neighbours. Business is a part of society, not apart from society. It exists to serve society. In order to do so, it needs to make a profit. Society gets many benefits from the operation of a free market. Without entrepreneurs free to pursue profit and growth we would have far less innovation. Yet businesses always need to remember that they are granted a licence to operate by society and society can take that licence away. It just becomes far more complicated in a global age. There is no global government. How complicated this all becomes is evident in current battles between the UK and the USA over the taxation of Google and Apple and the other internet giants. In the end I predict that society – or societies – will regain some kind of control over the behaviour of giant companies. xiv

This what Milton Friedman never understood. In his mind, business was one compartment and what it did could be isolated from society. Government could remedy the negative impacts of business. Today, the debate about the role of the stae and government is disappointingly oversimplified.

In the meantime, the state can be effective but it has to be subtle, not heavy handed. My father understood the law. He understood how it could establish conditions in which people could be free to act and rewarded for acting morally and penalised for acting badly. In Chapter 8 of Entrusted Ong Boon Hwee and I draw on best practice from around the world to describe the stewardship role of the state.

Fifth the company has always been a social institution, alongside an economic one. Work is important to our wellbeing. We need to be doing things that satisfy our sense of worth and our sense of meaning. You cannot create better companies serving better purposes unless you create the right foundations in the workplace. This implies that leadership matters. And that you treat people as ends, not means. More John Lewis, less Amazon warehouse.

Conclusion

You will remember that the name Goyder has its origins in forestry. Think about the best way to manage woodland. We can chop down the trees and harvest the wood for an immediate cash benefit, and then, as is happening in many places, replace the wood with a cash crop that pays more shore term dividends while impoverishing the forest as a carbon sink.

We could insist on a rigid view of what we want the trees to be like and have a monoculture of similar trees planted in rows. We can make the forest floor ruthlessly tidy, eliminating all the fallen branches that shelter the bugs and beetles. But that would be to ignore the true conditions for abundance in the forest. Let alone the wider value of the forest, and the plants and wildlife that thrive in it and contribute to its richness.

The full importance of the forest to us depends on its diversity, its webs of interdependence, and the wider social value that it has to those who use it. The health of a forest is not achieved simply by trying to maximise the growth of the individual trees we plant and chop down. True richness lies in its wider ecology. And for the forest to continue to be healthy in the future, we have to plant now, knowing that the benefits will only be felt after this generation is gone.

The same is true of business and investment. The wealth creation system is there to serve life now and beyond our lifetimes. It will only do so if it learns to balance present and future, and takes a holistic view of the relationships and communities which represent its wider ecology. Finance and markets and competition are servants, not masters, of this process.

True stewards are the ones who take responsibility for the condition of the whole wood. That’s the real Goyder message – Father and son. It is the central message if we care about our grandchildren.

i Entrusted: Stewardship for Responsible Wealth Creation. Ong Boon Hwee and Mark Goyder. World Scientific 2020

ii Signs of Grace, George and Rosemary Goyder Cygnet Press 1993 pp 15-16

iii The Future of Private Enterprise George Goyder Blackwell 1951

iv For more on the weaknesses of Friedman’s thinking see pages 8-18 of Entrusted: Stewardship for Responsible

v Leviticus 25 8-13 World English Bible

vi George Goyder CC Desai Memorial Lecture, Administrative Staff College, Hyderabad 1978 p 5

vii The Responsible Company George Goyder Blackwell 1961 p 8

viii George Goyder CC Desai Memorial Lecture P6

ix The Responsible Company George Goyder Blackwell 1961 p88 x The Just Enterprise George Goyder Andre Deutsch 1987 p 95

xi Entrusted op. cit. pp2-3

xii Financial Times 7 March 2020

xiii Prosperity; Better Business Makes the Greater Good Colin Mayer Oxford University Press 2019.

xiv These issues were the subject of the Tomorrow’s Global Company Inquiry in which Tomorrow’s Company brought together leaders of global businesses and NGOs to develop their vision of the global company of the future. https://www.tomorrowscompany.com/wpcontent/uploads/2016/05/Tomorrow_Global_Company_Challenges-and-Choices.pdf