This was originally published in 2002 but includes a new introduction which was written in 2008.

Tomorrow’s Company

In 1993 the UK’s Royal Society for the encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce (RSA) initiated an ‘Inquiry into the role of business in a changing world’. The inquiry began by bringing together 25 of the top businesses in the UK under the chairmanship of Sir Anthony Cleaver. The objective was to develop a shared vision of the company of tomorrow. The subsequent report, published in 1995, challenged business leaders to change their approach. It focused attention on the issue of how to achieve sustained business success in the face of profound social and economic change.

The report called for companies to apply what was termed inclusivity to their relationships. “Only through leadership and deepened relationships with – and between -employees, customers, suppliers, investors and the community will companies anticipate, innovate and adapt fast enough, while maintaining public confidence.”

Following the involvement and feedback of more than 500 companies in the UK, Tomorrow’s Company was formed as an independent business-led think tank. In the years following the publication of the report, Tomorrow’s Company helped move inclusivity from idea into action. It was described by USA shareholder activist Bob Monks as”…the world’s leaders in articulating specific policies and programs to assure corporate functioning on a human scale”. Over the years Tomorrow’s Company has become international in its impact working to create a future for business which makes equal sense to staff, shareholders and society.

Following the collapse of Enron, there were many debates about the causes and Mark Goyder and Tomorrow’s Company were deeply involved in these. 6 years later the same process took place in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, and many of the lessons from Enron do not appear to have been learnt.

Tomorrow’s Company continues to champion the central role of values in corporate leadership, governance and risk management. Just as the Agenda for Action for directors in the 1995 Tomorrow’s Company report offered boards a basis for identifying and preventing an Enron-style erosion of values, so the 2004 Report Restoring Trust warned that a financial system which lost of sight of the principle of ”Do no harm” to its ultimate customers was sowing the seeds of its own destruction – and over-regulation. The closing words of “Lessons from Enron” remain equally true

6 years later as we pick up the pieces of the financial crisis.

“The company is a living system. Employees are its life-blood. Management is the

heart which keeps the blood pumping. Strategy is the brain and measurement

and communication the central nervous system. Culture is the DNA. Leadership and

continued entrepreneurial energy are its soul and spirit. Governance and accountability

are its rhythms and disciplines, like exercise, a means of keeping this living organism

fit and lean. Unless we understand governance in this wide context, we will continually

fail to manage risk, sustain performance and earn trust. “

What can we learn from Enron?

Enron is an extreme case. The scale of shareholder value destruction is still to be counted. The fraud and the linked shredding of documents by one of the world’s leading accounting firms, are still being investigated. But can general conclusions about good governance be drawn from Enron, or is it an isolated case, an exceptional scandal?

There are many views about Enron and the lessons to be learned. We have heard about the role of the auditors and the Audit Committee; differences between the UK principle based and USA’s rule based system of accounting; the need to separate audit from consultancy and the role of the non-executive directors. In recent speeches and media interventions, Peter Wyman of the Institute of Chartered Accountants of England & Wales has been telling us that there is no systemic failure; that if this had happened in the UK the accounts would have flagged everything that was going on. I don’t think this is good enough.

I find the current debate extraordinarily narrow. What it ignores is the reality that a company is a living entity, not a machine. Consider a human analogy. If we want to help someone to stay lean and healthy, we have to do more than merely take his or her pulse. We have to understand the risks to their health and their motives and characteristics that may put at risk our attempts to make them healthier.

The accounting and audit systems are useful sources of information about the health of a company. But on their own they provide no guarantee of that health. They will not tell you about the motivations driving the behaviour of managers, or the likelihood of anyone acting decisively to deal with uncomfortable outcomes from the audit.

The existence of a group of non-executive directors may seem reassuring, alongside the panoply of independent committees such as the auditor and the remuneration committee. But take two companies with similar financial performance and governance arrangements. In the first shareholders may find nothing to lose sleep over: in the second they may find a disaster waiting to happen. The differences are human. Who dominates whom? What are the pressures to massage the results? Who dares to ask embarrassing questions? What are we here to achieve – the earnings we promised this year or value in the long-term? What is the way we all behave round here?

I was recently visiting a large quoted company, which was involved in an acquisition that had recently turned seriously sour. All kinds of cost overruns and customer claims started to emerge in the year after the deal was done. I asked one of its directors what he had learned from the experience. He told me that he was dissatisfied by the way they had gone about their due diligence. To have done the job properly, he believed, they would have had to have uncovered the underlying culture and behaviours of the organisation. As he had got closer to the acquired business over the past year, he had discovered that it had a culture in which people were terrified of admitting mistakes and therefore accustomed to covering things up. The usual due diligence would not have worked. The questions they should have asked, which they never asked, were about the ethics of the organisation and the appetite for bad news. Any organisation scoring low marks on these criteria could not be regarded as having trustworthy management information and the existence of traditional audit would have been no protection. Or, as he summarised it to me:

“A culture of fear is always a danger sign you should look for in your due diligence. If people are afraid, they learn to cover up bad news. ….we had no tools to look for this.”

The Sunday Telegraph (3rd May 02) gives another example:

“Lord Hindlip, the chairman of Christie’s, has admitted that he had prior knowledge of the price-fixing arrangement with Sotheby’s which scandalised the auctioneering world. …Lord Hindlip said he ‘knew something of what was going on’ with regard to collusion by the two companies, which has left two Sotheby’s executives facing jail in America. ‘It was such a blinding failure’ he said. ‘It was perfectly obvious it wasn’t going to work. Well perfectly obvious to me it wasn’t going to work. ‘I told them [the other executive] I didn’t think it was very clever idea.”

This is not new. The common feature of nearly every corporate disaster is that afterwards, you will find good people inside the organisation who will say, ”If anybody had asked me I could have told them something was not right.” It was true in Marks & Spencer, in Maxwell, in Christies and it was true in Enron where the FT tells us that executives kept asking how on Earth the rest of the company could be making money if it was managed as their part was managed.

That is why reviewing the technicalities of auditing and accounting is not enough and certainly will not tell us whether “it could happen here”. Take a closer look at Enron.

Avoiding another Enron

“Respect. Integrity. Communication. Excellence”

These, we are told, were the stated core values of Enron. They were the words that appeared on banners in Houston. But, as a recent Financial Times report by Joshua Chaffin and Stephen Fidler shows, they do not describe the behaviours through which people in Enron would be rewarded or promoted. Employees say Mr Lay’s true interest was performance. The flaw was that performance, as defined by Enron, was limited to actions that boosted the company’s bottom line – and ultimately its stock price.

“There were no rewards for saving the company from a potential loss. There were only rewards for doing a deal that could outwardly be reported as revenue or earnings’ says one former employee. FT, (9th April, 02)

A savage peer review process, called the Performance Review Committee, had the effect of instilling fear into people who might otherwise have challenged the integrity of the off-balance sheet arrangements. People worried that if they negotiated too hard on behalf of Enron with the ‘arms length partnerships’[1] (which had been set up to transfer risk from Enron’s balance sheet) they would suffer because the people responsible for the partnerships were also responsible for the peer review. An aggressive clique of ambitious young managers was promoted to run the new businesses created by Enron.

“These guys understood the game which was get earnings, get earnings, get earnings” said one former employee. ‘They knew how to use mark to mark[2] accounting and aggressive projections.”

This is an old, old story and there will be more, unless we seriously apply an inclusive approach to governance. How could non-executive directors have managed their risk and the risk carried by the shareholders and stakeholders whose savings and livelihoods were being jeopardised? At the moment all the argument is about the failure of the Audit Committee to spot the conflict of interest between consultancy and audit. Much less attention has been paid to a far more common-sense line of questioning that could have been adopted by any non-executive director.

Way back in 1995 the Tomorrow’s Company report suggested boards (executives and non-executives) should ensure that the following questions were being asked.

Company purpose and values

- Have we adopted a clear statement of purpose?

- Have we adopted an explicit statement of values which indicates how the company will conduct business and behave in its key relationships?

Key relationships

- Do we know which relationships are crucial to the success of the business?

- How do we ensure that the company is maintaining consistent and open two-way communications with people in all relationships?

- How do we ensure that the risk of failure is being managed?

Success model

- Have we adopted a success model for the company, which demonstrates how value is added?

Measurement

- Do we review the company measurement system annually against its ability to support our goals, purpose, values and key relationships?

Reward system

- Do we review the reward system against its ability to reinforce business goals and motivate the right behaviours? Do we monitor positive behaviours such as teamworking and empowering?

- Do we seek reports on levels of behavioural risk in key areas of the business?

Fiduciary responsibilities

- Are we satisfied as fiduciaries that we are acting in the interests of the general body of shareholders as it exists from time to time and not simply current shareholders?

These questions are not technical. They are common sense. They point to a behavioural audit trail. They ask; what do we demand of people? How do we know if we are getting it? What kind of performance are we looking for? If it is purely financial, what is our protection against fiddling and fraud? The subtext is: never mind the fine words: what kind of behaviours actually get people bonuses and promotion round here? Never mind the carefully honed numbers that keep fund managers happy. What is really going on in the business and how robust is it? Non-executive directors need to know what kind of behaviours get rewarded in the business. They need to have their own ways of connecting with the real DNA of the business. How often did any non-executive director in Enron ask a question such as:

- Can we say that respect is one of our key values?

- How do we audit whether we live by that value?

- Can I see the recruitment criteria for senior positions? Are the values reflected there? “

- Can I see the criteria used by the performance review Committee?

- Are the values reflected there? Or are they simply words?

- What is the secret to getting on in your career in this organisation?

A non-executive director in Marks & Spencer five years ago, before the collapse in the company’s share price, could if he had asked the right people, have discovered that the HR department wanted to do an employee attitude survey, but felt unable to do so, because they feared that they would not be allowed to publish the results if these were unfavourable. These are the danger signs in organisations that have become too complacent or too narrow in their view of success.

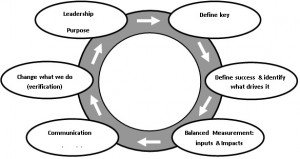

The truth is that purpose, values and relationships are the leading indicators that tell you something is wrong before it hits the bottom line. If you focus on financial indicators, you will be too late. The Enron story reminds us that many people inside the business know that things stink long before the whistle is blown. And people on the edge of the business have the opportunity to manage their risk by following the behavioural audit trial. Of course we need proper protection against conflicts of interests and greater seriousness and independence in the conduct of the Audit Committee. But as long as we see governance in narrow terms and seek new technical rules to guard our companies against fraud, these things will continue to happen. We need a values-based, as well as a compliance-based, approach to governance, based on what CTC calls the ‘Virtuous Circle of Governance’.

Part of the reason for failures like Enron, is that our investment system is losing its grip on the concept of long-term shareholder value. The investment community has shifted the emphasis from shareholder value to share price. Companies can be congratulated for increasing shareholder value when all they have done is (often temporarily) boosted the share price. Companies can be accused of destroying shareholder value when the share price goes down. Yet, as the technology boom reminds us, the share price is heavily influenced by opinion, assumptions, sentiment and investors’ beliefs about which way other investors will jump. It has become an increasingly poor indicator of the underlying health of the business.

There can be no better example of this subversion of shareholder value than the Marconi case. A few months ago Marconi’s former CFO gave an account of his actions in the Financial Times. He produced figures to demonstrate that, in terms of total shareholder return during his term of office, the company had really done quite well. His biggest regret, he went on to say, was that he had failed the board by not selling the company to someone else when the share price had gone down to £7, well off its high of £12 but long before it collapsed to under 20p. In other words, the value-destroying decision to put all the eggs in the telecomm basket was not the biggest mistake. The real failure was not cashing-in in time by finding someone else willing to take on this basket case. This is what is sometimes described as the ‘greater fool’ school of shareholder value: it doesn’t matter how foolish your strategy, as long as you can find a greater fool to take it off your hands.

This is a corrupted view of shareholder value. It concentrates not upon the organic capacity of a company to create future value, but on the potential to come out ahead after undertaking a series of transactions. It is instructive to observe the difference between Marconi and BAE Systems, the company formed from the acquisition by British Aerospace of all the GEC Marconi defence operations. Here are two companies that restructured themselves. In BAE Systems there was a leadership who believed in making profound changes in the attitudes and the competence of the people running the business, so that the new company was ready for the challenges that lay ahead. In Marconi the attention was on reshuffling the portfolio and not on the development of the capabilities of those running the business.

The primary pressures to which most business leaders have to respond are the perceived shareholder pressures. Without an inclusive approach, the risk is that what shareholders will get is what Enron gave them – earnings today and nothing tomorrow.

There is an expectations and timescale problem. As a German working in the USA put it to me: “You Anglo Americans are all the same. You want the harvest at Easter.” Research last year by Fortune magazine showed that of the top 150 American companies over the last 40 years, only three or four have been able to sustain earnings growth at an average of 15% a year for a 20 year period. But, as Terry Smith has pointed out (article in FT Business News, 3 Feb, 02), this does not stop many CEOs from claiming that they will double earnings within five years, equivalent to compound growth of 15% a year. CEO tenure has shortened. Rewards for executive performance are increasingly linked to share price over periods significantly shorter than the investment cycle of the industry or the time taken to effect cultural change or to implement strategy. And, of course, we have stopped rewarding CEOs for long-term performance. More and more we are giving them stock options – an incentive for them to manipulate upwards the price of the business rather than its ultimate value.

Some questions for Boards

So here is the agenda which I would like to offer to the many bodies that will play a part in ensuring that the Enron story is not repeated here. You are the company’s ethics and risk committee. Clear your agenda so that there is time for the serious examination of corporate values and the gap between what is preached and what is practised in your company. It may tell you more than the report of the audit committee. Ask repeatedly what kind of behaviours and what kind of managers get on round here? Do the answers fill you with confidence? If not, dig deeper.

Some questions for Institutional shareholders

Re-examine your time horizons. What kinds of performance are you rewarding and how durable is it? Are you incentivising people to boost the share price without regard to the future? Challenge the remuneration. Is it one-dimensional? If it is, how can you be sure that you are getting real or cosmetic improvements?

Question CEOs about the kind of atmosphere and culture they seek to create in their companies. See if they are managing the risks that go with big rewards for performance. You are right to invest a lot of credibility in CEOs and teams who deliver what they promise. But how much do you trust the earnings reported to you? What about cash and what about the underlying health of key relationships in the business? Are you encouraging a game of presentation, rather than underlying substance?

Some Questions for Pension trustees

Question the more active of your fund managers. What are they doing to promote the underlying health of the businesses they invest in and to manage the risk around values, culture and

governance? How are they rewarded? Are they encouraging an approach that delivers expected numbers at the expense of building value for the future? Is this what you want?

Some questions for Company secretaries

Open up the AGM. Encourage awkward questions as an insurance policy and a sign that the CEO and Chairman of your company are role models for open behaviour.

Some questions for the Remuneration Committee

Is your approach to performance one-dimensional? If it is focussed on total shareholder return – over what timescale? How are you protecting tomorrow’s shareholders against today’s creative accounting? Where in the remuneration system are you sending signals that results are not to be achieved at any price to the values and integrity of the organization?

Some questions for Business Journalists

How often do you ask the CEOs you profile about the things they are doing to ensure the business is still robust in ten years’ time? Do you ask them about the ethos of the business? Is the emphasis exclusively on performance and the next few quarter earnings? What about following the behavioural audit trail? Do you talk to employees and customers and look at the underlying health of the organisation that is expected to continue delivering these results?

Conclusion: an inclusive approach to governance and risk management

Lessons from Enron

The company is a living system. Employees are its life-blood. Management is the heart which keeps the blood pumping. Strategy is the brain and measurement and communication the central nervous system. Culture is the DNA. Leadership and continued entrepreneurial energy are its soul and spirit. Governance and accountability are its rhythms and disciplines, like exercise, a means of keeping this living organism fit and lean. Unless we understand governance in this wide context, we will continually fail to manage risk, sustain performance and earn trust.

[1] ‘Arms length partnerships’ were apparently separate businesses set up by Enron managers and directors to trade with Enron without the usual accounting transparency: they were effectively conspiracies by Enron managers against Enron shareholders

[2] ‘Mark to mark’ accounting is another name for booking anticipated profits before they have been earned.