Entrusted – stewardship for responsible wealth creation

By Ong Boon Hwee and Mark Goyder

About the book

Our system of wealth creation is at a crossroads. It has contributed to economic and social progress. Yet it has also fuelled many problems, from climate impacts, and air pollution, to digital manipulation, and the invasion of privacy. In many parts of the world, there are demands for government action to restrain greed, irresponsibility and short-termism.

But what about positive solutions? How do we define the contribution that we all want business and investment to make? That is the challenge to which Ong Boon Hwee and Mark Goyder respond.

They argue that if our societies are to be set on a less damaging course, we will need every ounce of human ingenuity –– the inventiveness of entrepreneurs, the dynamism of companies, the adaptability of markets. We need to be better at valuing the future and rewarding those whose work will benefit future generations. We need a better form of capitalism, one which, while promoting competition, is there to serve and not dominate; to respect human beings and not exploit them; to nurture our surrounding environment, and not destroy it.

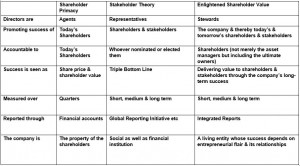

Shareholder primacy is becoming a discredited dogma. Stakeholder theory doesn’t get to grips with the entrepreneurial energy that any healthy economy needs. A better capitalism will only be achieved by injecting the spirit and principles of stewardship into the decisions of investors, business leaders, regulators and citizens. The authors draw on their combined experience, combining the perspectives of East and West, to offer a vision and agenda for responsible wealth creation.

Stewardship means that we manage, nurture, and grow what has been entrusted to us so that we hand it over in a better condition to the next generation. This book offers ideas and guidance for people in all areas of business and across all roles — asset owners, asset managers, investors, shareholders, board directors, management, policymakers, and regulators. It is a handbook for all those willing to play their part in responsible wealth creation, now and for future generations. It says to each participant – consider what you have been entrusted with, and then decide what you are doing about your stewardship responsibilities.

About the authors

Ong Boon Hwee is CEO of Stewardship Asia, a Singapore-based thought leadership centre that champions responsible wealth creation across Asia. He has previously held senior roles in Singapore Power, Temasek Holdings, his own leadership and strategy consultancy, and in the Singapore Armed Forces.

Mark Goyder is the founder of Tomorrow’s Company, a London based business think tank. Tomorrow’s Company paved the way for the redefinition of directors’ duties under UK company law, pioneered the importance of purpose beyond profit, and the stewardship role of boards and investors. He has 15 years’ experience as a manager in manufacturing companies.

Endorsements for Entrusted

“This is an important book at a critical time. The paradox is that while our problems are complex and require long-term solutions our world is increasingly short-term focused. The only solution is to embrace stewardship so that we leave organisations and the world in better shape as a result of our efforts. This book lays out a powerful approach to do so.”

Antony Jenkins, CEO 10x Future Technologies and formerly CEO Barclays

“With the Shareholder Primacy paradigm now under intense and growing pressure, and the more recent Stakeholder approach proving to be a necessary but not sufficient driver of economic transformation, it is time to revisit humanity’s deep wisdom on how to run a business for the ages – in the form of stewardship. In their wonderfully insightful book, Entrusted, Ong Boon Hwee and Mark Goyder illuminate pathways to a post-Friedman world which potentially works for all.”

John Elkington, Founder, SustainAbility and Co-Founder, Volans

“Entrusted” is a wonderful resource, a treasure trove of explanations, insights, examples and tools to help us all become better stewards

Oonagh Harpur , Independent Non Executive KPMG UK LLP

“This is a book for anyone with a real interest in thinking deeply about the purpose of companies. The authors chart a course for responsible capitalism, or stewardship. Governments, business leaders, and investors should read it. Like the authors, I believe strongly that business leaders and owners must consign the aberrant shareholder value primacy to the dustbin of history and build a better model that recognises the wider purpose of business and its societal connection.”

Robert Swannell, Chair, UK Government Investments and former Chair, Marks & Spencer.

“I have known Mark Goyder for more than a decade. He is a deep thinker about the way organisations work, their responsibilities and their impact upon society. Purpose and values within a business together with an indomitable belief that business should be a force for good are cornerstones of his approach. In this East-West collaboration these convictions shine through. In writing ‘Entrusted’ Ong Boon Hwee and Mark Goyder have combined powerfully to challenge conventional thinking and offer positive solutions.”

Dr Andy Wood, OBE, DL

Chief Executive Officer, Adnams Plc.

“I have always believed that individual wellbeing depends on a sense of living in harmony with oneself and with others, Before I read this book, I hadn’t been convinced that the business community understood this deeply. Yet, with telling examples from East and West, this book shows business at its best, and demonstrates a way forward to which companies, investors, governments and citizens alike can contribute. It’s a vital agenda for rebuilding trust and tackling a widespread sense among citizens that they have lost control over a system that is not working for them.”

Anthony Seldon, Vice-Chancellor, The University of Buckingham and author of Trust (2009) and Beyond Happiness (2014)

“Capitalism needs a reboot. We need companies to show their human face. That’s easy to say. What I like about ‘Entrusted’ is that Mark Goyder and Ong Boon Hwee combine an inspiring vision for business with practical recommendations for boards, investors, governments, and individual savers. This is an agenda that can and must make a difference in the digital age.”

Jason Stockwood, Vice chairman of Simply Business and author of Reboot: A Blueprint for Happy, Human Business in the Digital Age

What does Entrusted Say About:

A Stewardship Mindset

A stewardship mindset reflects the following key ideas:

– People are interested in profit, but are motivated by more than just money

– Business, finance and the market should be seen as servant, and not master

– Business is part of society, not apart from it

– Neither market forces, nor imposed regulation, will deliver the right outcomes for society on their own. Without the enlightened self-interest of responsible wealth creators and entrepreneurs, the market system will degenerate into a see-saw between greed and bureaucracy.

– Business is conducted to meet human and social needs, and should be judged by the total value it creates in contributing to human well-being. Of which financial value is one part.

Capitalism and how to make it better

How do we make our system of wealth creation no less adventurous, but at the same time more human, more honest, more responsible, more inclusive, more engaging, and more respectful of the needs of our grandchildren? How do business leaders, investors and policymakers create, lead, and influence companies that we can all have trust in and be proud of, and thereby show the way to a better form of capitalism, one which serves society as well as feeds and safeguards future generations?

Laws, rules, taxation, and incentives are part of the answer. They are the hardware of the system that channels money into productive and profitable businesses. But what about the software or ‘heartware’? That is, the attitudes and behaviours that permeate our system of wealth creation? This is where stewardship plays its part. In this book we introduce – or to be more accurate, reintroduce – the concept of stewardship and describe how, in practice, it has helped some organisations address the problems of capitalism and how it will continue to do so in the future by bridging the broken connections among companies, shareholders, and society.

The clients and beneficiaries of investment institutions

‘It is too superficial to say that the client is only interested in making as much money as possible, quarter by quarter. …Good steward investors start by defining over what time horizon the client needs a return, and this gives them a much clearer sense of the investments likely to achieve this.

Clients and beneficiaries are real people. They have their own priorities and expectations and it is the job of investment professionals, like any other professional, to find out what they are, not speculate about what they might be.

The role of ordinary citizens

There is an emerging groundswell of action by citizens who see the damage being done by ‘business as usual’. Greta Thunberg leads and symbolises the rejection by young people of the current, damaging course that we are on. Extinction Rebellion is a movement of growing importance.

Yet there are more direct routes to influence which connect – or have the potential to connect – citizens to the heart of the wealth creation system.

In crude terms the investment community needs to recognise that the ultimate shareholders are all of us who save beyond the confines of our own community or family. Apart from the very poorest, citizens are therefore also shareholders, and beyond their financial stake, their wellbeing is associated with the success or failure of the wealth creation system. The savings and investment system is there to serve citizens as a whole. It is directly accountable to those who have a financial stake, and is morally accountable to every citizen.

The investment priorities of the individual or the group of individuals cannot be taken for granted. It is too superficial to say, as many people assume, that the client is only interested in making as much money as possible in the short term. Everyone wants a return. But at what cost, in terms of risk and impact? In an effective stewardship value chain, every investment fund in question will make clear its investment objective, its time horizon, and its approach to assessing whether the company is capable of making lasting returns.

Investors who try to present investment priorities as a choice between ethics and superior financial returns are deceiving themselves and misleading their clients. Stewardship involves a search for approaches that will equip a company to make long-term returns while meeting the wider expectations of savers or investors.

The book describes the part that concerned citizens can play through their involvement in the system. It shows how the ultimate beneficiaries of pension schemes or clients have the opportunity (which they often fail to take) to issue instructions to their fiduciaries about the returns they want from their investment, and the risks that they would prefer to see associated with their investment.

Even taking the most exclusive and narrow approach to the problem, if the owners and providers of capital are to protect the financial value of their investments into the future, they have to safeguard the natural, human, and financial capital with which nature and previous generations have endowed them.

In other words, there needs to be a discussion about how the client defines value.

Corporate Governance

Corporate governance is much misunderstood and, at times, more harm than good has been done in its name. Governance has its place, but it should not be allowed to stand in the way of innovation and entrepreneurial flair. It has become over-complicated and over-prescriptive. Yet in essence, it is very simple. It is a set of arrangements for keeping companies honest and accountable. Directors are the stewards in charge, entrusted by the owners, shareholders, and investors to take care of the assets and hand them on to their successors in better condition. In fulfilling their responsibilities, they need to see the company as a living system.

Populism

There will be critical choices to be made by companies seizing the high ground in robotics, artificial intelligence and bio-engineering, Will they place respect for ethics and human dignity ahead of short-term profit? Or will they take Milton Friedman’s view that they can do whatever the law permits and leave it to the state to set ethical boundaries? If this happens, ordinary citizens will feel that technology is out of control, deployed by large companies for profit-making, irrespective of a wider purpose. This will strengthen the belief of many people that the system is not working for them. Investors and boards have a crucial role in in holding a company’s feet to the fire and insisting that it spells out clearly its purpose, values, and approach to the longer term, and more importantly, ensure that it walks the talk.

Without the stewardship agenda described in this book, we will be left wringing our hands, anxious but ultimately helpless as these issues overwhelm us. The critics are right. An irresponsible and short-term wealth creation would endanger the planet and undermine the values that have underpinned stable societies in the East and West. In the absence of a stewardship spirit and its push for responsible wealth creation, the political debate about capitalism may well tilt to an extreme end of the spectrum – towards extreme forms of populism on the right, or extreme forms of socialism on the left.

Sustainability

‘Natural disasters triggered by climate change have doubled in frequency since the 1980s. Violence and armed conflict cost the world the equivalent of 9% of GDP in 2014. Lost biodiversity and ecosystem damage cost an estimated 3%. Social inequality and youth unemployment are worsening in some countries around the world, while on average, women are still paid 25% less than men for comparable work.

Rapid economic growth may have lifted many out of poverty, but this does not necessarily address the issue of widening economic and social disparity. Business leaders, together with consumers and governments, bear their share of responsibility for inflicting harm, either directly or indirectly. By the same token, we all have a central role to play in making things better. ‘

Purpose of Business

Conventional answers to the question ‘What is the purpose of business?’ tend to be divided into two opposing camps. The stewardship mindset offers a third way of answering the question:

Short-termism

The chairman of a listed company was reflecting on the boom years leading to the 2008 financial crisis. He regretted that he had failed to resist the pressure from institutional shareholders to increase the company’s debt and pay out more to those shareholders. This decision left the company dangerously exposed when the cost of credit was increased. He did not think it was the right thing to do at the time. He just did not know how to resist. He felt he had failed in his stewardship. The pressure to meet quarterly earnings targets is estimated to have reduced research and development spending and cut US growth by 0.1 percentage points a year.

Facebook, Amazon, Apple and Google

Connecting people in massive numbers can lead to results that are the very opposite of what was intended from increasing connectedness. They are not the kind of relationships that promote greater trust. It may be no coincidence that people’s willingness to trust fellow human beings has sharply declined over the last generation. Through the Internet, we now have very powerful companies being given freedom by the state and encouraged by their shareholders to make a great deal of money out of the creation of these digital communities. They are proud of creating but accept little or no responsibility for the worst consequences of the design and character of these communities. In due course, governments or supranational communities may decide to intervene. In the meantime, there is a role for all those involved in the stewardship value chain in tackling this challenge. It is the institutional investors and the directors that they elect to the board of companies like Facebook whom ordinary citizens ought to be able to rely on to hold a company to account in living up to its promises and to what others expect of them.

Fiduciary Duty

Fiduciary duty is, in simple terms, the duty of being a steward or trustee. That involves balancing many considerations and often striking the right course between conflicting claims. It does not mean shutting down your conscience in the belief that you have a duty to maximise profits in any way that is legal. Fiduciary duty extends all the way along the value chain that connects savers and investors with companies.

The fiduciary duty of institutional investors

In order to do justice to their fiduciary duty, steward investors must undertake two tasks. The first is to find out so far as is practical what the individual or individuals see as desirable investment performance. In other words, how do they as shareholders interpret value? The second is to factor into investment criteria the issues which will have an impact not only on the value of the investment but on the ability of the beneficiaries to enjoy its fruits.

The fiduciary duty of directors of a company

Under most forms of company law around the world, directors owe their duty to the company, not to shareholders. The board is, in most systems, elected by shareholders. But that does not mean that directors are there to follow every whim of every shareholder.

As good stewards and fiduciaries, directors have a duty to promote the success of the company. By doing that, they will create value for shareholders. They have to find the right balance between results today and results in the future.

Often fiduciary duty is used as an argument to defend short-termism and the plundering of a company for the benefit of immediate shareholders. Yet this has no basis in law.

The role of governments

Governments do not have any option. They are stewards by nature. Every government would acknowledge its obligation to be wholehearted and responsible in its management of the assets with which it has been entrusted so as to pass them on in better condition. This is the very definition of stewardship. The approach that the state takes towards wealth creation will; however, be a particularly vital determinant of its overall success. Government’s stewardship influences over wealth creation can both direct and indirect. Directly, with respect to the market the state acts as an investor, asset owner, asset manager, client and customer. Indirectly the state has the opportunity to be an enabler of responsible wealth creation, through making the rules and setting the rewards and penalties via regulation. It sets the tone, influencing the business environment through incentives and policy initiatives, and crucially, through leadership by example.

In the West, the debate about the role of government gets bogged down in Left vs Right arguments between free markets and state interference/planned economy. For example, in the UK in 2019 questions have been raised about whether the UK government should have intervened to prevent the travel firm Thomas Cook going bust.

It is important that governments do not bail out failed companies: otherwise they will be encouraged to take undue risk.

Yet, as the book explains, there are many places in the world, especially in Asia, where governments do play a more important role without interfering with market freedoms. The book describes ways in which governments delegate authority to sovereign wealth funds or state holding companies. The role of Temasek – a Singapore state holding company – in preventing an opportunistic and value-destroying takeover bid of food company Olam is one example.

If the UK government had followed the example of companies like Singapore, and set up state holding companies or sovereign wealth funds to invest with a long term focus, there could have been legitimate ways for the muscle of major investment funds to exercise stewardship earlier in the process in ways that stopped a company like Thomas Cook from taking on massive debt when acquiring other companies. And, having taken on that debt, Thomas Cook might still have been prevented from ultimate bankruptcy if its steward owners had insisted on the progressive paying down of that debt. Instead shareholders allowed the boards to base incentives on share price performance over too short a period, reducing the incentives for the executives to be prudent.

Once the market fails, the choices becoming more difficult. Yet even here, if the government sits at the centre of a spider’s web of influence through its different roles as shareholder, client, banker, and regulator, there is an opportunity for government ministers to be catalysts for co-ordinated action between these different functions. At present governments in the West tend to sit on their hands, as happened with Thomas Cook, or go to the other extreme, pay good money after bad, as has happened in an example like Amtrak in the USA.

Takeovers

Consider the contrasting fortunes of two well-known companies in the food industry, both confronted in recent years by an aggressive attack from the outside – Cadbury and Olam.

Once a bid was made, the board of Cadbury had a choice. In principle the board of directors, which felt that the Cadbury approach to business was worth preserving, and disliked the very different business culture of Kraft, could and should have rejected the bid on the grounds of stewardship and suitability, not price. But this was easier said than done. The Cadbury board was under intense pressure from shareholders, nearly half of whom were in the US. It would have needed the cornerstone support of loyal institutional investors.

Olam was originally headquartered in London but then relocated to Singapore in 1996. It filed an Initial Public Offering, in 2005, listing on the Singapore Stock Exchange. However, unlike Cadbury, it had a number of significant anchor shareholders. One of Olam’s anchor shareholders, Temasek, believed in the management of the company. It offered to buy the shares of any shareholder tempted to accept the takeover bid from Muddy Waters. As a result, the bid failed and the company was saved from being broken apart. It has since continued from strength to strength.

All listed company boards need to think about these risks to prepare long before danger arrives. They need to look at their current business model and consider the merits of having an anchor (steward) shareholder.

The ultimate defence against shareholder opportunism is to use the mandate process to force the intermediaries who put investor capital behind such approaches to check whether it is actually what the ultimate clients and beneficiaries want done with their money.

Leadership, Stewardship and Success

The decision that a leader makes to lead in the spirit of stewardship rarely stems from a cold analysis of the evidence. Great steward leaders display the courage of their convictions. There is, nonetheless, an impressive body of research evidence from Asia, Europe and the US that connects the elements and concepts of stewardship with enduring and successful companies.