Text of a talk given by me in Madrid on 13th January, 2017 to an audience of chairs, CEOs, NEDs, investors and advisors hosted by IC-A (the Spanish Institute of Directors).

In 1976 I went walking in the Spanish Pyrenees. As it happens, I was staying in the part of Spain that was home to the Mondragon group of Co-operatives, a fascinating and very successful experiment in pooling the financial and social capital of a region to invigorate its communities. What fascinated me was the way the combined savings of people in the region were so directly mobilised to meet its needs – products, employment, training and education, even personal finance and social care. The individual co-operatives were bound together by a bank – the Ceja Labral Popular (check).

I revisited Mondragon in 2005, as Tomorrow’s Company was developing its vision of Tomorrow’s Global Company[1].I felt then that the pressures of globalisation were making it harder for many of the Mondragon enterprises to stay competitive, and yet that the close alignment of finance to the ends and purposes of this community of enterprises gave it a better chance.

I have not kept up with the progress of Mondragon since then, but whatever its more recent experiences it remains a social and industrial experiment from which we can learn as we think about the future of capitalism and the companies of tomorrow.

My visit to Spain in 2005 took place at a time when we were all optimistic about the future of global capitalism. It had helped pull a billion people out of poverty. The inquiry team (of leaders from 11 global companies) set out a vision of global companies acting as a force for good in the triple context of economic, social and environmental challenges. It did warn of the dangers of inequality – as Davos is doing this year. It certainly focused on the growing climate threat. pointed out the importance of action by global companies working with civil society organisations to fill the vacuum left by the weakness of global institutions. It spoke of the unifying power of global companies. It gave countless examples of innovation that served society as well as shareholders, with a purpose beyond profit. At their best global companies bind together colleagues behind this a shared purpose with common values that transcend cultural or religious differences.

This felt like a more optimistic time!

Today we are learning about the ‘shadow side’ of the big global companies. Their impersonality; their capacity to be heartless, relentless in their pursuit of results at scale. Their ability to avoid paying taxes in the countries where they sell products and make profits. Their oppressive use of their purchasing power to delay payment to smaller suppliers. Even where they have formed framework agreements and committed to high labour or environmental standards, we are discovering that these may be hard to monitor and uphold. In 2015 as the UN struggled last year to rise to the challenge posed by the Syrian refugee crisis, I noticed that the entire humanitarian budget of the UN is equal to the profits Apple made in one quarter.

Of course there are elements of truth in both views of the global company. In the post Lehman, post Brexit, post Trump, post truth world, how do we shape capitalism so that it continues to be an engine of prosperity while better meeting the needs of society as a whole? Or in the words of the UK PM, so that it meets the needs of the many not the few?

22 years on from its birth, Tomorrows Company continues to struggle with these issues, working with the CEOs and CIOs and government policymakers. The power of this approach is twofold. It leads to credible, practical solutions, and it energises those who have searched for them to put them into practice.

Today I want to share with you our very ambitious agenda. It builds on 20 years of work. It will take time to achieve. It cannot be achieved by companies, or investors, or governments on their own. It needs a joint and systemic approach.

The agenda for change covers:

the well led company

the well-governed company

the well owned company.

And I conclude by talking about how this agenda can help us shape the capitalism that we need.

The well-led company

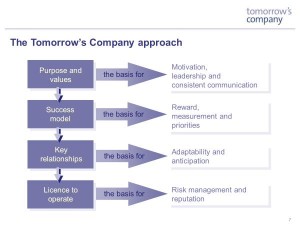

Purpose, values and relationships and are the foundation of the enduring success of any business. The stronger the awareness, positive identification with your purpose and values , and the trust of people you deal with, the greater the new business opportunities and the loyalty of the current ones. Leaders focus on living their values through their relationships. This is at the heart of success.

Let me give you one example which I learned through a former chairman of Tomorrow’s Company – Sir John Egan. He was a successful CEO of Jaguar who went on to run the British Airports Authority, of which Ferrovial is now the largest owner. Many of you will have used the rail link that connects the airport to central London. You may not know that there is a serious tunnel collapse which brought construction to a halt.

On the Monday morning after the disaster, John Egan called a meeting of designers, contractors, suppliers and all the part of the project. He told them that the project had a choice:

They could either spend the next year arguing about who was to blame, or they could agree to work together to ensure that in spite of this major setback the project was completed on time and on budget. This is what they agreed to do and the whole project became a case study in the Tomorrows Company approach. People came together to achieve a common purpose, working together according to share values in a way that they created far more value than would have been achieved by a more transactional or narrowly financial approach.

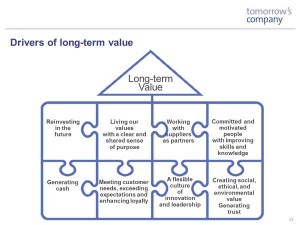

This approach was developed by an inquiry team of business leaders whom we brought together to think about the role of business in a changing world. They concluded that while financial returns are an outcome, it is clear purpose, clear values and strong relationships that are the foundations of long term business success. It is through relationships that businesses learn and adapt. Being close to society is not just a question of moral duty – it pays. Look at the research[2].

Companies which have endured the longest always have this in common: they know what they stand for, they stay close to society and learn through their relationships. They can be ruthless about changing their products but rarely change what is in their DNA. Companies which have endured to create most shareholder or financial value are those which hve been best at anticipating and responding to society’s needs and providing the people who work for them a real sense of meaning.

So, you might have thought that, in our governance of companies, we would be focused not only on financial performance, but on these underlying drivers of long term value.

The answer is that we are beginning to make progress towards that, but the progress has been slow. Boards often know that it is values, relationships and behaviour – how we do business – that is the most important. After many years in which Tomorrow’s Company has championed the importance of culture, the UK regulator, the Financial Reporting Council, has strongly promoted the importance of culture. Boards certainly see the costs when they allow people to focus on performance without any concern about the way performance is achieved. Look at Volkswagen facing a cumulative bill now rising above $10bn towards a point when this liability dwarfs all its assets!

But, especially in listed companies, they find themselves being pressurised to deliver earnings and share-buybacks. Earlier research by the US National Bureau for Economic research showed that over half of 400 executives would avoid initiating a project that would be very positive in terms of net present value if it meant falling short of the current quarter’s consensus earnings. Over the first 6 months of 2016 S&P companies paid out 112% of earnings in dividends and share buybacks.

We need boards to be leaders and not followers. That is why Tomorrow’s Company has developed the concept of the board mandate where directors sit down and define what their shareholders have elected them to do, what is the purpose and values and indeed desired culture and behaviours of the enterprise, and what is their risk appetite and what are their obligations to their different stakeholders.

Then instead of giving in to the insidious pressures from the markets or the media muttering about the share price, they and the CEO can with confidence concentrate on doing the right thing for the long-term success of the business. (insert reference to board mandate)

The well-owned company

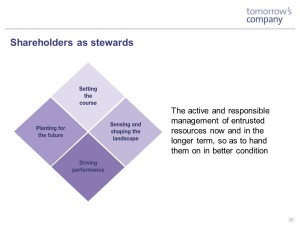

The best place to look for the Tomorrow’s Company approach to value creation is in the well-run, long lasting family business. Here each generation acknowledges that it has inherited the company and its values and relationships from its predecessors, and wants to pass it on better condition.

All of them follow the four principles of stewardship.

First – clarity.The owners give a clear mandate to the board, and the board give a clear mandate to the CEO. The CEO and the management are then free to get on with the task.

Second – continuous attention to improvement. Through the governance process the owners and the representatives on the board will still be challenging to ensure the company is not complacent, and to ensure that in its pursuit of performance it is not forgetting its values.

Third – good stewards look outwards – they sense change and they seek to be involved ins society in shaping change – for examples by working to achieve higher standards of behaviour in their industry. And finally, they keep a balance in their minds between short term and long term performance.

The future of capitalism

So how do we create the conditions in which society thrives as capitalism thrives?

To put it simply, we face a choice between two views of capitalism. Views which are most clearly seen in the listed company sector but which symbolise the assumptions we make.

One is the extractive view of capitalism

This treats companies as assets to be sweated. It measures success in terms of the cash returned to shareholders, not in terms of the investment made in the future growth, the benefits delivered to customers, employees or society. Its symbols are the electronic ticker screens relaying real time information about the share price, and the disproportionate rewards paid to advisory firms for securing a merger or acquisition without any link between those rewards and the future success of the merged enterprise – success which proves elusive precisely because enterprises are not assets to be sold, repackaged and sweated!

There is an alternative view of capitalism, which sees companies as human organisms, entities created by human beings to work with other human beings and apply human skill and technology to meet human purposes while making a financial return which also ends up going to human beings.

This view is best seen at work in enduring family businesses. In these the current generation are naturally thin king of their role as stewards of the assets that they have inherited for generations to follow. They are not interested in sweating todays assets because they don’t intend to sell their shares and they care about the health of the enterprise and it relationships and reputation which are the foundation for future success.

There is no reason in principle why listed companies should not live by these principles. Some -often those like Tata or Toyota where the influence of the founding family is still strong – still do. But the pressures of the capital market pushes them in the direction of extractive capitalism. The fund managers are rewarded for relatively short term performance. They put their pressure on the CEOs. The CEOs start to question why they should reduce shareholder returns today for a better tomorrow when average tenure is less than four years. In the USA, for example, while share buybacks have rocketed, S&P companies are applying a hurdle rate to new investments of 18% when interest rates have dropped to 2 or 3%.

The listed sector is only a part of the total corporate landscape. Businesses and their leaders in many other sectors diferent qualities. But its attitudes and behaviours dominate the debate – look at the arguments about remuneration! – and set the tone.

There isn’t time here to deal with all the other policies that would be adopted by effective government to promote the principles of stewardship as companies are formed, and grow up.

One thing is very clear: we need to see more innovation in corporate form and more hybrids. Look at Handelsbanken, a listed company that sets aside a proportion of its profits into a trust fund (the Octagon Trust (check) that holds share on behalf of employees and creates a capital sum for those -employees when they leave the company. That is stewardship capitalism – putting something in to the company to promote its long-term growth.

Many people have asked me how I can remain optimistic after the events of the last year. I would argue that the last year makes the Tomorrow’s Company agenda more urgent. The rhetoric around Brexit was around people taking back control. I believe that we need to develop a form of capitalism in which employees and citizens can feel that companies are in some way accountable to them, not faceless monsters. Hence my belief in a strong regional approach – I mentioned the Basque Region’s Mondragon earlier and I’ve been learning today about the city of La Coruna and the way everyone came together to work for a better city – businesses, investors, local authority. That’s an approach that |Tomorrow’s Company is developing in the UK, working in East Anglia with leading businesses and its partner the University of East Anglia.

The UK’s new Prime Minister has talked about the need to create an economy that works for the many, not the few. This is exactly what companies will achieve if they focus on relationships.

Let’s take the setbacks of the last year and see them as reasons to improve our leadership; to redouble our efforts to inspire and enable business to be a force for good in society. There’s no contradiction between this objective and creating long term value for shareholders. On the contrary, it is only by a focus on purpose, values relationships and the long term that we can hope to deliver growing, enduring companies. And it is these growing companies that will be able employ and excite the next generation, and achieve enduring returns while developing to pay for the infrastructure, the nutrition, the health care and new education and training for the huge environmental, social and economic challenges that face as we race into the Fourth Industrial Revolution.

[1] See Tomorrow’s Global Company report

[2] See Living Tomorrow’s Company – Rediscovering the Human Purposes of Business ch