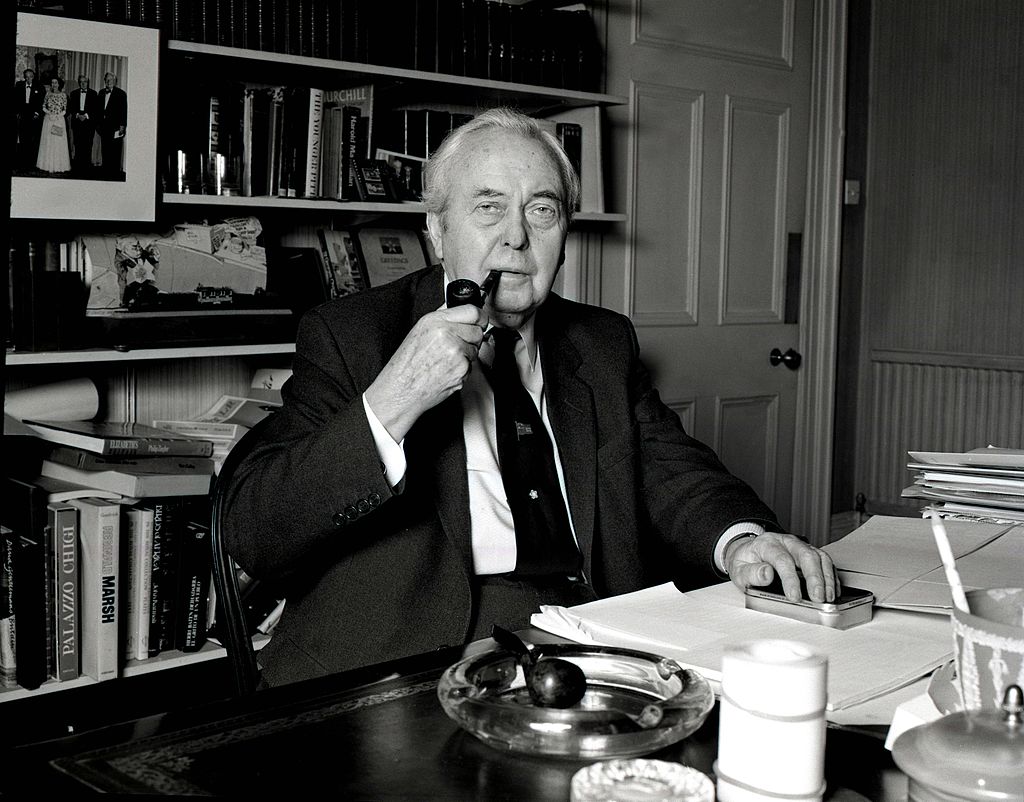

When I was 11 years old my grandmother gave me a book token for Christmas and I spent it on two paperback biographies. One was about the racing driver, Graham Hill. The other was about Harold Wilson, Labour’s recently elected Prime Minister.

To many Labour traditionalists, Harold Wilson was a traitor. From Ramsay MacDonald to Keir Starmer, the same charges have been made against nearly every leader who has attempted to modernise the Labour Party and broaden its appeal. Only a few have succeeded with a narrative of renewal.

Clement Attlee had his positive part in the wartime Cabinet to help refresh Labour’s appeal. (The word ‘socialism’ only appeared once in the Labour manifesto then, whereas the words ‘nation’ and ‘people’ were used repeatedly, we are told in his most recent biography.)

Harold Wilson spoke of modernising fuddy-duddy Britain through the ‘white heat of the technological revolution’. Tony Blair rebranded his party as ‘New Labour’ and removed the old commitment to nationalisation of industry from the party membership cards.

What should Keir Starmer do? What story can he tell and what solutions can he offer that will convince both party members and uncommitted voters that he ‘owns the future’; that he both understands how the world is changing and has a programme that is equal to the challenges ahead?

His New Year speech gives us some clues – with its 2030 ambition for 100% clean energy and its (welcome) focus on devolution of power away from Westminster and its insistence on a longer-term focus. He talks about ‘a new path to growth’; ‘a robust private sector creating wealth in every community’; ‘new technology unleashed by public investment and private enterprise’. He hasn’t yet spelled out the policies by which he would make this happen.

I’ve just been reading ‘A View From the Foothills’, the superb (Labour) ministerial diaries of Chris Mullin MP. His entry for 1 January 2000 seems prescient today.

‘Our main problem, of course, is not other people’s wars. It is that we have invented an economic system which is consuming the resources of the planet as if there were no tomorrow… All over the democratic world, politicians increasingly follow rather than lead…. Maybe, just maybe, this will be the century in which we learn to reduce, reuse and recycle our waste, develop benign sources of food and energy and stop burning up the ozone layer…Who knows there ought to be money to be made out of going green, in which case capitalism could enjoy a new lease of life.’

Chris Mullin was writing in a period before the full urgency of the climate crisis was recognised and before the NHS and social care systems had been allowed to decay to their present critical condition. Yet those two urgent challenges make a new government’s agenda for facilitating long term wealth creation even more important.

Such a vision would commit government to be a good steward of everything that the current generation will pass on to its children and grandchildren. It would offer practical ways of encouraging well-owned, well-led businesses to flourish – companies with commitment to their region and their communities, measured not only by their financial performance but also by the value they create for society. Such a programme would:

1. prioritise human capital – see human diversity, population health and early-years learning (along with biodiversity and natural capital) as the foundation stones of economic and planning policy, rather than its dividends.

2. extend official measures of economic success to include the creation of social goods and social value and human wellbeing indices in parallel with GDP.

3. make the wellbeing of future generations a cornerstone of all policymaking and regulation as now happens in Wales.

4. encourage the responsible stewardship of companies, promoting investment in mutuals, social enterprise, employee ownership and family business and other forms of ownership which support the creation of social value.

5. use the £300bn public procurement budget to prioritise long term contracts with companies of demonstrably solid ownership and good character (See BS95009 as a starting point).

6. shape the tax system to

a. incentivise long-term investment

b. discourage the short-term ‘flipping’ of companies by private equity firms

c. penalise investment in housing for speculative rather than social purposes

7. raise more tax revenue from, among others, the very rich, the non-doms, the carbon emitters the sugary food producers and arbitrageurs in the casino economy.

8. build on existing institutions such as the British Business Bank to ensure investment funding is available on a regional and local basis to help entrepreneurs grow companies in line with these priorities

9. crack down on London’s role in facilitating corruption and money laundering

10. lay the foundations for a circular economy, for example by encouraging regenerative agriculture and localising food and energy production

11. decentralise decision making and reinvigorate local authorities while pouring investment into early-years’ health and education.

12. use citizens’ juries and similar consultation processes to involve the wider population in planning for the long term renewal of cities, housing, and transport.

Call me naïve by all means. Yet I believe that such a manifesto would not only appeal to business but also to many of those undecided citizens whose votes Keir Starmer needs.